-Nilaa Maharjan Logpoint Global Services & Security Research

Executive Summary:

- QakBOT, also spelled Quakbot is an old banking trojan active since 2007 that has seen a rise as multiple threat actors are caught using it in their malspam campaigns, following brief inactivity in early 2022.

- It has been seen spreading primarily through attachments and links in targeted spearphishing attacks. The most common variant used HTML Smuggling to serve an embedded password-protected ZIP file containing a shortcut file(LNK) which exploits several living-off-the-land (LOLBins) to download the Qakbot payload.

- Other TTPs include the use of Microsoft Word Documents and leveraging the “Follina“ exploit, bundled with LNK which executed Qakbot DLLs.

- This new emergence uses multiple, simple, yet effective, defense evasion techniques against static detection methods.

- Discovery commands were observed in multiple instances before take-over, possibly prepping for multiple backdoor and lateral movements.

- Attackers have slowly started venturing outside the banking sector and started targeting health, infrastructure, information technology, and many others.

Over the past few months, companies such as SpaceX, Go West Tours, Commercial Development Company, Inc., Furniture Row & Visser Precision, Kimchuk Inc., and Hot Line Freight Systems have been the victims of QBot-related attacks and data leaks – some more impactful than others.

- Qakbot is modular and evolves with each new threat actor making it very hard to detect – making use of existing binaries, vulnerabilities, or advanced defense evasion techniques.

The prolific modular information-stealing malware known as Qakbot, also spelled Quakbot and Pinkslipbot, was first identified in 2007 and has been around for well over a decade. Due to its design and the efforts laid in by various threat actors, it is a common tool used in multiple known ransomware campaigns. Historically considered a banking Trojan and loader, it’s evolved multiple times and sees a resurrection every few years associating itself with new vulnerabilities, actors, and industries. The pattern itself has been dubbed “QBot“.

The operators are occasionally known as “Gold Lagoon” and have been seen conducting operations since its establishment, with activity seen in various nations on most of the continents. However, the malware is not associated exclusively with any actor or group.

Trend Micro’s periodic detection rates show that in the first half of 2020, QBot accounted for almost 4000 unique detections, of which 28% were targeted to the Healthcare and Public Health(HPH) sector. The attacks subsided eventually as the latter half only saw 8% targets towards HPH.

QBot itself contains multiple modules:

- Password Grabber Module: To steal credentials

- hVNC Plugin: To allow an external operator to remotely control the device without the victims’ knowledge even if the user is logged in

- Cookie Grabber Module: To steal browser cookies

- Web-Inject Module: To inject JavaScript codes into websites (primarily financial institutions)

- Email Collection Module: To extract emails from local Outlook clients and used them as a basis for further QBot phishing campaigns

- Core Capabilities include:

- Reconnaissance

- Utilizes process injection to run a series of discovery commands:

- whoami /all, arp -a, ipconfig /all, net view /all, netstat -ano, net localgroup

- Utilizes process injection to run a series of discovery commands:

- Lateral movement

- Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI)

- Privilege escalation and persistence

- Creation of scheduled tasks

- Registry manipulation

- Credential harvesting

- Attempts to enumerate credentials from multiple locations

- Targets browser data (including cookies and browser history)

- Data exfiltration

- Specifically exfiltrates emails

- Other payload delivery

- Cobalt Strike

- Often used by threat actors to deliver additional payloads or sell access to other threat actors.

- Reconnaissance

Case Study

There have been multiple QBot attacks. Notably on JBS, the largest meat producer in the world, and Fujifilm, a Japanese multinational conglomerate in early June 2021. Despite the fact that the two attacks, their victims, and jurisdictions are vastly different, a strong commonality reveals the same pattern and perpetrator – the REvil gang, who may have used the QBot malware to accomplish the initial infection operation.

First, we’ve witnessed instances where QBot infection timing correlated with REvil attack timing in the past. In other words, their attack – most frequently a data leak – followed a specific temporal pattern following the original QBot infection. REvil usually stays in the network for two to three weeks after launching a sophisticated attack against a primary victim, something AdvIntel identified during this same interval between QBot infiltration and the REvil breach when researching REvil-related issues. Additionally, the fact that the two crime groups’ TTPs and operational models make cooperation logical and natural.

On the one hand, QBot (as a botnet) is notorious for establishing itself by collaborating with as many top-tier ransomware gangs as possible. A typical botnet organization will have one relationship with ransomware as a service (RaaS) gang, occasionally two, but QBot deviates from this trend because they have always aimed for large partnership expansions.

Other botnets had only one liaison on the ransomware side, QBot had several. Dridex, for example, had DopplePaymer; TrickBot botnet had Ryuk; Zloader had DarkSide. At the same time, QBot was infected with Egregor, ProLock, LockerGoga, Mount Locker, and other ransomware groups.

REvil, unlike other ransomware groups, is known to diversify its attack tools. Usually, each ransomware group has its preferred tool, for instance, one infrastructural vulnerability, or one specific botnet. However, REvil aimed at covering as many attack surfaces as possible. Like many groups, they started with RDP exploitation, but they never stopped there.

In 2021 (REvil’s year of rapid diversification) they announced investments in specialists in BlueKeep vulnerability, PulseVPN exploitation, and Fortigate VPN exploitation. They have clearly expressed their interest in the novel Microsoft server CVEs, then in TrickBot malware, and then, finally, in a direct purchase of network access from underground.

The re-emergence of QBot in 2022 has been driven by Black Basta which is a whole new mess. Since its inception in April, Black Basta has gained attention for its recent attacks on 50 businesses worldwide, as well as its use of double extortion, a new ransomware method in which attackers encrypt secret data and threaten to disclose it if their demands are not met. Trend Micro has an entire report covering the TTPs by Black Basta which includes the trojan QakBot as a means of access and movement, as well as using the PrintNightmare vulnerability (CVE-2021-34527) to do privileged file actions.

As with all Emerging Threats blogs, we include a report. A recent example of the previously mentioned attack, including a detailed analysis of the malware sample, the execution chain, and the observed tactics and techniques, is included in the download of the report.

Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs)

Putting aside the fact that QBot is an efficient information thief and backdoor on its own, many RaaS providers have been found employing QBot variations to get access to corporate networks before delivering ransomware.

Previously distributed via Emotet, the recent resurgence shows that the attacks are rising through very targeted malspam email campaigns. These most recent operations start with the distribution of an HTML attachment and email thread hijacking.

When the file is opened, it drops an archive (.zip) that includes an Office document, a shortcut file (.lnk), and a .dll file inside of a disk image file (.img). The DLL will be executed by the LNK to launch QBot. The document will then load and run an HTML file that contains the PowerShell exploit CVE-2022-30190 used to download and run it. But since the vulnerability has been patched, attackers are making use of native binaries through LOLBins. The attackers are clearly not taking any chances with multiple points of failure in the hopes that at least one of these strategies will work.

Another variation of the attack substitutes a .iso file (another form of disk image file), which once again contains a .docx file (Word document), a.lnk file, and a.dll file, for the .img file in the zipped bundle.

After making changes to the parent malware, QBot’s operators have been observed leaving a version tag in their samples.

For Example:

{

"Bot id": "obama182",

"Campaign": "1651756499",

"Version": "403.683",

}Before infected Windows devices shut down, the QBot samples from a December 2020 update activated their persistence mechanism, and they automatically deleted all traces when the system restarts or awakens from sleep. This enables the persistence mechanism to be engaged too quickly for security software to identify when it is shutting down. Similar strategies have been employed by Dridex and Gozi, including the use of several encryption algorithms. This hides its functioning and information from potential victims as well as security software. The sample was also observed making an attempt at legitimate process injection-based obfuscation. Once the victim’s computer has been infected, it is compromised, and due to QBot’s lateral movement skills, they could pose a threat to other machines on the local network.

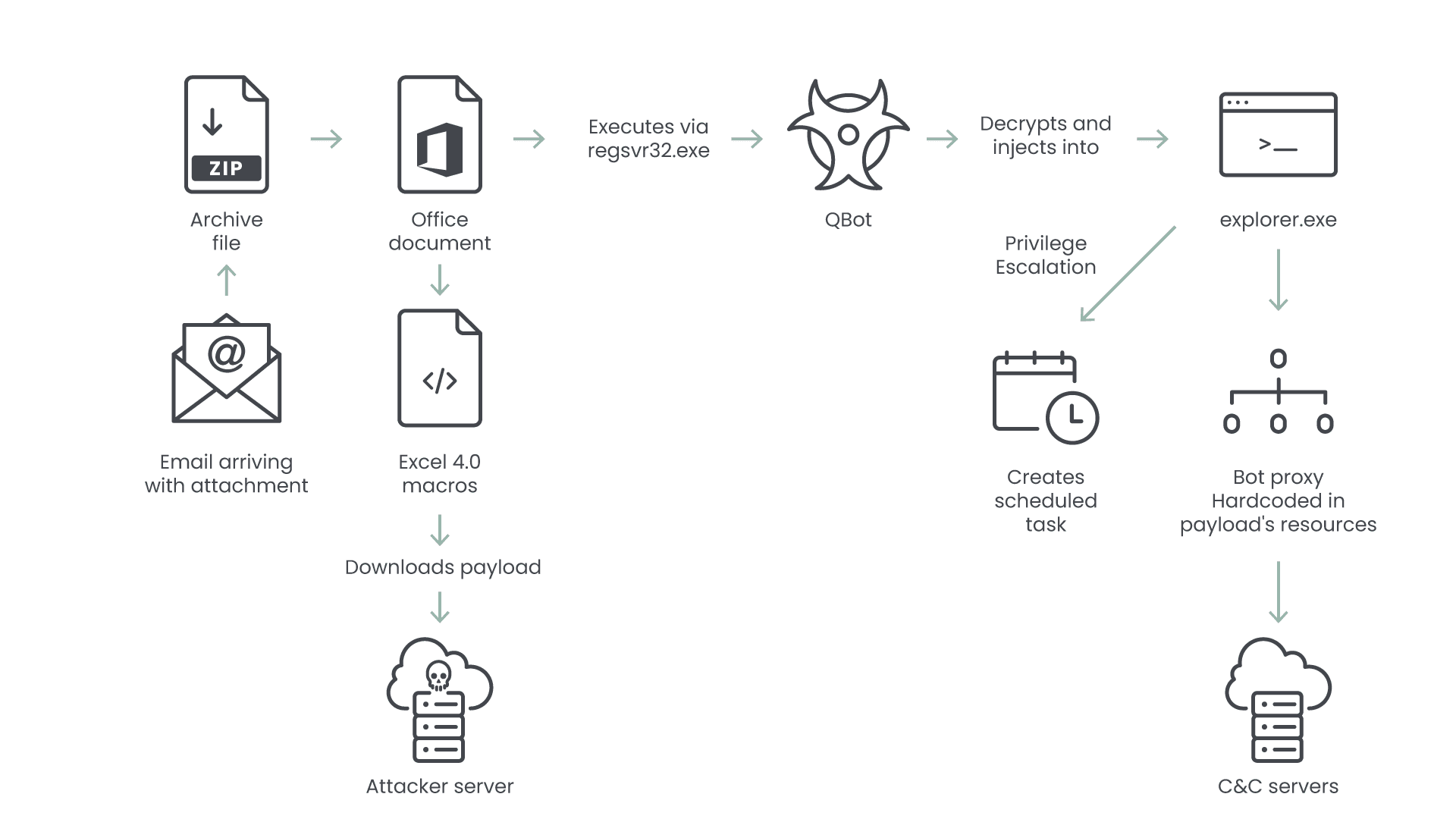

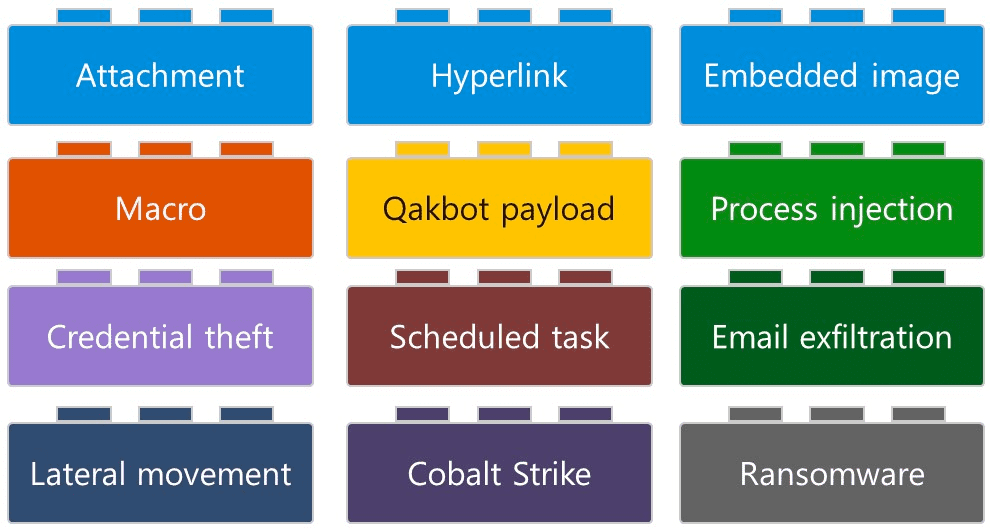

The building blocks of QBot attacks. Source: Microsoft

Despite all the variations available and new changes expected, the family of Qakbot is identified by some of its use of similar building blocks. A Universal Plug-and-Play(UPnP) module embedded in QBot transforms the infected hosts without direct internet connectivity into intermediate command and control (CnC) servers and uses them as a botnet. The CnC then downloads further modules which include:

- Password Grabber Module: To steal credentials

- hVNC Plugin: To allow an external operator to remotely control the device without the victims’ knowledge even if the user is logged in

- Cookie Grabber Module: To steal browser cookies

- Web-Inject Module: To inject JavaScript codes into websites (primarily financial institutions)

- Email Collection Module: To extract emails from local Outlook clients and used them as a basis for further QBot phishing campaigns

QBot has been known to make use of other dependencies than what it packs. These include:

- PowerShell: to manipulate files, decode, embed, and inject Mimikatz binary into the memory.

- Mimikatz: for credential theft, certificate theft, reconnaissance, pass the hash attack, and lateral movements.

- LOLBins: native windows binary files that reduce the need to upload tools to perform malicious activities.

Besides these, QBot has been seen downloading additional ransomware such as Prolock, Egregor, and REvil/Sodinokibi. As the CEO of Advance Intel was seen quoting, “A network infection attributed to QBot automatically results in risks associated with future ransomware attacks“

Mitigation

As QBot and other ransomware have been a steady line of attack for the past couple of years, each organization should have a baseline prevention and mitigation procedure by now. CISA‘s Alert (AA21-131A) DarkSide Ransomware: Best Practices for Preventing Business Disruption from Ransomware Attacks provides a good outline as well.

- Require multi-factor authentication for remote access to OT and IT networks.

- Enable strong spam filters to prevent phishing emails from reaching end users. Filter emails containing executable files from reaching end users.

- Implement a user training program and simulated attacks for spear phishing to discourage users from visiting malicious websites or opening malicious attachments, and re-enforce the appropriate user responses to spear phishing emails.

- Filter network traffic to prohibit ingress and egress communications with known malicious IP addresses. Prevent users from accessing malicious websites by implementing URL block lists and/or allow lists.

- Update software, including operating systems, applications, and firmware on IT network assets, in a timely manner. Consider using a centralized patch management system; use a risk-based assessment strategy to determine which OT network assets and zones should participate in the patch management program.

- Block zip file attachments and disable the execution of macros.

- Limit access to resources over networks, especially by restricting RDP. After assessing risks, if RDP is deemed operationally necessary, restrict the originating sources and require multi-factor authentication.

- Set anti-virus/anti-malware programs to conduct regular scans of IT network assets using up-to-date signatures. Use a risk-based asset inventory strategy to determine how OT network assets are identified and evaluated for the presence of malware.

- Implement unauthorized execution prevention by:

- Disabling macro scripts from Microsoft Office files transmitted via email. Consider using Office Viewer software to open Microsoft Office files transmitted via email instead of full Microsoft Office suite applications.

- Implementing application allow-listing, which only allows systems to execute programs known and permitted by the security policy.

- Monitor and/or block inbound connections from Tor exit nodes and other anonymization services.

- Deploy signatures to detect and/or block inbound connections from Cobalt Strike servers and other post-exploitation tools.

If your organization is impacted by ransomware or QBot incident:

- Isolate the infected system.

- Turn off other computers and devices. Power off and segregate any other computers or devices that shared a network with the infected computer(s) that have not been fully encrypted by ransomware.

- Secure your backups. Ensure that your backup data is offline, secure, and free of malware.

During this research, from the static and dynamic analysis, we uncovered multiple files, domains, and botnet networks that are still active in the wild. All artifacts are provided as lists and the associated alerts are available to download as part of Logpoint’s latest release, as well as through Logpoint’s download center.

Customized Investigation and Response playbooks were pushed to Logpoint Emerging Threat Protection customers.

The report containing the analysis, infection chain, detection and mitigation using logpoint SIEM and SOAR can be downloaded from the link below.